Risk & Experimentation

We solve important and/or difficult problems. Good delivery means effectively finding the right solution and managing risk. To do that, we employ experiments - things that help us build the right thing and build it right. But it can be hard to know which methods to employ when. We are successful when we are committed to a higher mission objective, but use experiments and risk management to find the best path(s) to meet that need.

We solve important and/or difficult problems. Good delivery means effectively finding the right solution and managing risk. To do that, we employ experiments - things that help us build the right thing and build it right. But it can be hard to know which methods to employ when. We are successful when we are committed to a higher mission objective, but use experiments and risk management to find the best path(s) to meet that need. Experimentation-related terminology commonly thrown around include: discovery, MVP, prototype, pilot, problem-solution fit, fail fast, iterate, alpha, beta, A/B test, mockup, wireframe, user validation, research spike, proof of concept, lean startup, lean impact, continuous learning, feedback, analytics. Let's try and bubble this all up to 3 questions in order to dive into what is appropriate when.

Note: Equivalent logic applies to whole "products" or major features/initiatives that aren't truly a separate product.

1. What is the magnitude of value?

Some solutions are truly mission critical and will impact the lives of many. Other solutions are necessary but far less critical. Even within the same product we may be building the forms used by 100k people a month to grant access to life-altering benefits while also creating some admin screens used for occasional housekeeping by a handful of in-house government staff.

Not all features require the same level of process and polish. Coupled with always-limited budgets, we must set a level of effort appropriate to the situation - as too much effort on a less-critical feature robs resources for more important functionality. We triage which functions get the 'white glove' touch vs. 'good enough'. That is not "cutting corners." Rather, it's managing resources and it is very important.

2. Where is the risk or unknown?

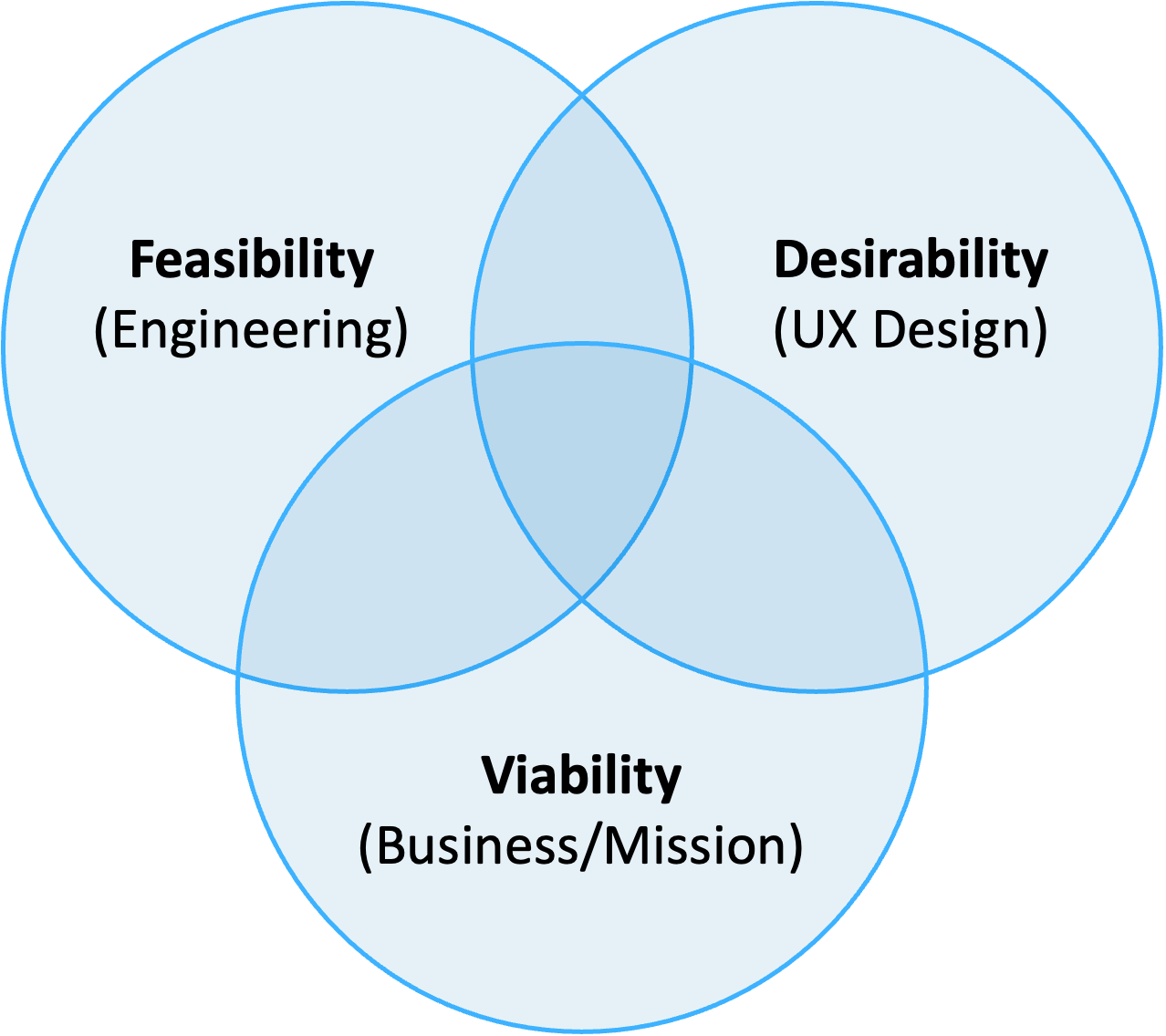

The product management concept of the "3 lenses" provides a framework for the typical categories of unknowns in digital products. Pictured below, gaining a holistic view of the product requires us to consider the feasibility (can be built), desirability (will be valued by users), and viability (has a sustainable business model). As a starting point, you need to be clear on where major risk resides.

Feasibility: We aren't certain of which technical solution to choose, need to confirm if certain technologies or architectures can meet specific performance needs, or need to know if the functionality can be achieved at all.

Research spikes are short and low-effort (often less than 1 engineer for 1 sprint) explorations on some very specific feasibility question. Example: will PostgreSQL JSONB fields support the specific query needs we have? I could research the docs, perhaps spin up a local version and seed some data to demonstrate a couple key queries. If we confirm that it cannot be done, we can move along and no longer consider that option.

Engineering or architectural proof of concepts (PoCs) are more involved, trying to meet a vary targeted subset of requirements. Code is throw-away, so we simplify all other typical solution constraints (we don't need robust testing, infrastructure automation, etc.). Example: will AWS Lambda and SQS give us all we need for managing a data pipeline including managing failed transactions? We can set that up in a sandbox environment that is not "production grade."

Desirability: We don't know if users will want to use the product at all, or perhaps aren't sure which of many design directions might best serve their needs. Worse yet, sometimes we think we know what users want. If we haven't validated those ideas, we are at risk of spending a lot of effort building the wrong thing only to figure that out after launch. Even if the solution idea comes from a user or SME, validation of desirability is still often warranted.

User research tests higher-level ideas or generates insights about user desires and motivations. It prunes some possible directions (if users don't care about a workflow happening more quickly, then we don't need to chase down solutions for streamlining). There are many research techniques that are best covered elsewhere.

UI prototypes come in various forms (low-fidelity/high-fidelity mockup, wireframe, click-through prototypes). We use prototypes to simulate key aspects of system interaction. We can learn that the interactions, terminology, and layout are intuitive and help users achieve their goals (or not). It can be challenging to convey a more sophisticated experience that depends on data or other "real app" functionality (see Alpha prototypes).

A/B testing allows us to test two alternative user-facing options in a production app. Some portion of users are presented with option A, some with option B, and then we can see which yields better results. The options are typically relatively minor variations (even as minor as button design in some cases). This is especially appropriate where real live users are the most valid form of feedback, and where there is high value in incremental improvements. Example: you are fine tuning a benefit signup form UI and instructions and trying to reduce drop-off at each step.

Viability: We don't know if this product will be sustainable at all. For commercial products, this is basically about the business case - that it can generate profit. For government, it is generally about mission impact, policy boundaries, or funding.

Business/product analysis (i.e. just researching stuff and talking to people) can help to understand the mission priorities and validate the potential impact and importance of the product. In general, we want to know the answer to a few questions. Is this addressing a high-priority mission objective? Is it likely to impact actual outcomes? Is there a funding model to support it over time? Are there any legal or policy constraints?

Minimum Viable Products (MVPs) are meant to answer the viability question (but the term is often used to refer to what I consider a Beta or Version 1.0). The idea - coming from the lean startup world - is to build just enough to validate "product-market fit" which is essentially the business model of the product. As a result, you either continue to build out the product and business or "pivot" to a different business model. In government, we don't do big pivots (going from serving retirees to serving young parents), but might make product pivots. Example: when the government wanted to distribute COVID tests, they created a simple web form to let anyone request them. If this fell flat, they could have ditched that product and moved to a different approach toward the same outcomes - such as proactively sending requests to everyone's address on file w/ the IRS.

Cross-cutting Experiments: Some techniques cut across all 3 lenses.

Alpha prototypes are an in-progress product, but not production-ready. We can learn a lot by giving some users access to a demo environment where they can interact with realistic data and functionality.

Beta prototypes are production software, but limited to a subset of users or provided as a parallel option alongside an existing product. The "beta" label also communicates a lack of full commitment - i.e. this product won't have full support expectations, may change in major ways, or may be discontinued altogether.

Version 1.0 is the first release of a production system - or at least the first post-beta release where we are confident the product won't have major "breaking" changes (i.e. removing or drastically changing core functionality). This isn't a true "experiment" but rather defined here to differentiate from alpha/beta/MVP versions. The "1.0" designation is a recognition that the launched product is still a source of learning and expected to improve or expand over time.

3. Can we craft an effective experiment?

Any experiment helps us learn something specific and intentional about a major area of risk. To do so well, you should:

Determine the level of importance and resource for this product/feature.

Set a clear purpose for the experiment including a risk or unknown that is important to success. Tie it to a decision not yet made.

Set up a clear hypothesis before the experiment, including an upfront definition of validation, and communicate that with stakeholders.

Make decisions based on the results.

If we have clarity on the above points, then we're going to get value from the experiment.

What should we avoid?

Some of the antipatterns that violate the above 3 questions are common in government (and no doubt non-government) technology. Many involve a bias toward pre-determined direction. We get attached to an idea and a vision of something great and helpful. We are not truly looking for information that invalidates that direction. It's a common human tendency, a.k.a. confirmation bias. You get excited about a new car you'd like to buy, and shrug off articles that complain about reliability issues.

False economy: Why invest time in research and PoCs if you can just get on with building the darn thing? Classic IT project management involves some upfront planning so you can write code right the first time, avoiding rework or changes in direction. If we're honest about what we don't truly know, then we see the business case for resolving those unknowns. If we haven't independently validated that users want the thing, and are about to invest $1 million in building said thing, then let's invest $50k to make sure we're going in the right direction.

Pre-determined decisions: Central to the philosophy of agile, lean startup, or related methods is that we can only plan so much of our path. We are better off being good at adapting to change than being good at fortune telling. (Perhaps we would be better off with the latter if it were feasible.) When already dead-set on an approach, we can say we're launching an MVP or beta, but that's not honest unless we are going to change our approach based on the results from those experiments.

One-size thinking: Some features have a huge impact on customer outcomes. Those likely benefit from a robust process of discovery, problem definition, and solution definition. But, we don't need to use every method for every situation. Many features don't warrant extensive user research, or performance testing, or any number of other risk-reduction techniques. We must align efforts to the risks and magnitude of the specific product.