How to be a Contractor

Historical Context

Government contracting has a history as old as government. The dynamics of our environment, even the ones that seem odd or bureaucratic, are often reactions to problems of the past. Much of the ‘red tape’ associated with winning and delivering contracts is there to avoid corruption and cronyism. The “beltway bandits” stereotype has roots in reality. The government cares about integrity of the process and wants to avoid certain pitfalls. Sometimes it can seem like overkill, but understanding how the lines are drawn helps us be more effective.

Sidebar: Why do contractors, and not federal employees, do most hands-on technology work? Many government agencies do have some talented in-house technologists. Even those with a strong team still have capacity needs that go beyond the quantity which they can deliver. Most agencies only have staff to oversee work. OMB Circular A-76 defined certain kinds of work as “inherently governmental” and thus only able to be done by federal employees, and that other work should be contracted out with the belief that it is more efficient. It may make sense for some technology work to be contracted, but as government moves into the digital age, the digital service delivery capability is becoming more inherently governmental as it is so intertwined with delivery of policy. At some point, there may be fewer digital services contractors and more feds. However, we are here to help fill that gap in the meantime.

We deliver work under contracts with the government. Some of the fundamentals include:

- Procurement. The process for the government to buy services is rather controlled with the goal of maintaining integrity in that process. Requests for proposals (RFPs) are advertised publicly. The government accepts proposals and evaluates them impartially against a set of pre-defined evaluation criteria. Communications are very controlled to not give unfair advantage. We can talk to government counterparts about potential work before an RFP is released, but must be careful about discussing a live RFP (though really it is the government staff that bear much of the risk of improper communication).

- The Contract. We enter into a legally binding contract with the government to deliver a set of services. This authorizes us to perform a specific scope of work. We cannot do work that is outside of those bounds. If it makes good sense for the contract to change, a contract modification can occur.

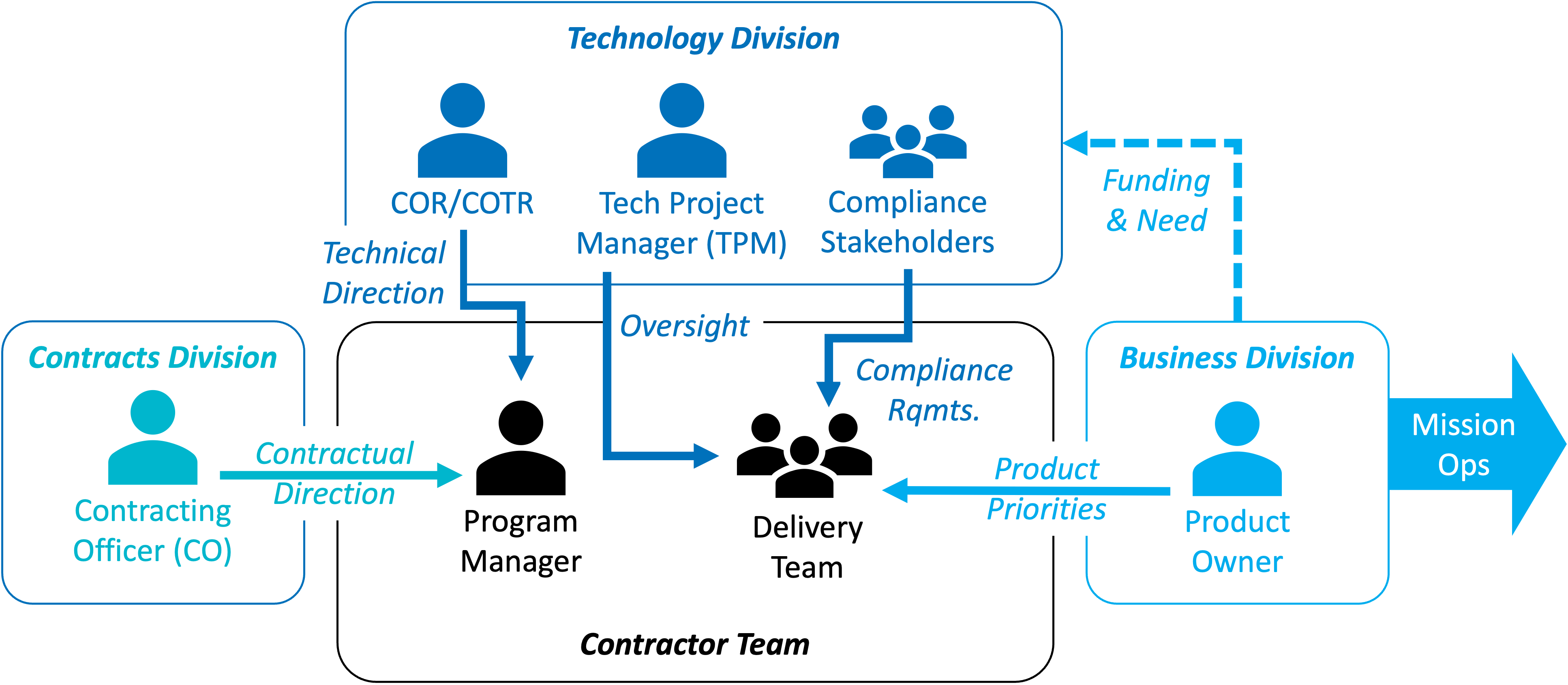

- Contracting Officer (CO). Contracting Officers are specially trained and have special authority to enter into contracts. No other government employees can authorize work to be done. Even if a Department Secretary said “do this and you’ll get paid” – that wouldn’t be truly in effect until done by a CO. Questions of scope and dollars are the CO's domain.

- Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR)/Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COTR). COs aren’t experts in the technical scope of the work. The COR/COTR role provides technical direction within the scope of the contract. They can’t obligate more money to the contract or assign entirely new areas of scope, but they can direct contractors to work on specific priorities within the scope. Other stakeholders within the government organization don’t necessarily have that authority. However, there is nuance as to what is technical direction, and other stakeholders make some decisions that impact our delivery. In a well-functioning contract, the COR is a partner of ours to navigate stakeholder requests that may be out of bounds.

Key take-aways: If the customer is talking about entirely new scope or funding, then the CO needs to authorize that before we can work on it. If customer staff, such as a product owner, are asking us to do things, we should be looping in the COR to get their buy-in.

Typical Stakeholder Mix

Contracts and client organizations vary. However, it is very common to have an “IT” contract that exists to help serve a mission need. In an imaginary but typical customer organization, the top-level organization includes a Contracting Division that manages all contracts, a Technology Division charged with implementing digital capabilities and multiple Business Divisions that operate specific mission areas. The Technology Division manages our contract and is the “buyer” from our perspective. The Technology Division procures our services to help them serve the Business Division, which is their internal customer. The Business Division in turn provides funding to the Technology Division for that purpose. Our team interact with a CO from the Contracting Division, a COR from the Technology Division, Technology Division Project Managers (TPM), Business Division Product Owners (PO) and SMEs, and a number of compliance-oriented Technology Division stakeholders (Security Branch, Accessibility Branch, etc.). We primarily are partners with the TPM to collectively serve the PO while staying in line with mandates from the compliance stakeholders.

Typical Rules of the Road

In addition to the specific roles of a CO and COR, there are some typical expectations of how contractors and feds interact. It depends on the nature of the contract:

- Managed service: In the most hands-off model, the government wants a turn-key capability managed entirely by the contractor. In this case the contractor would control the solution, technology choices, procure and mange hosting, provide product support, etc. (We have not delivered on such a contract.)

- Solution Delivery: The government requests a solution to a specific mission need. We propose a product solution including an architecture and approach. We deliver that into the customer environment (hosting, policies, etc.).

- Capacity Delivery: The government doesn’t buy a specific product or solution, but want to procure the capacity of one or more high-performing cross-functional teams. This allows them to have the flexible product/feature scope to align to modern product management and agile models. (This is our most common type of contract.)

- Staff augmentation: When the government has a competent digital service capability, they may simply need to ramp up team capacity. They might value experience and incremental improvement ideas, but don’t need a wholesale method. (We sometimes engage in these with high-maturity, high-performing customer organizations.)

Contract Vehicles

Agencies sometimes compete and issue standalone contracts. More typically, work is awarded under a contract vehicle. This doesn’t always make a substantive difference to the work, but can shift the competitive playing field.

- Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ): This is a contract vehicle with one government agency. The contract itself has no work or funding. Rather, task orders are where the “real work” occurs. Task orders can be competed under a multi-award IDIQ. Some agencies may have IDIQ contracts with 5-15 companies for related scopes of work. This helps them qualify a short list of companies and streamlines the process for competing task orders (as compared to separate contracts for each).

- Government-wide Acquisition Contract (GWAC): Some contracts are available to any government agency. These typically have anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand awardees. Contracting officers can then use the GWAC contract to procure services. The benefit is that some of the grunt work is handled at the GWAC level (incorporating various terms and conditions, doing some basic qualification of the firms). The problem with GWACs is that they limit competition to a subset of companies, and the means of qualifying companies is generally low-value. If 300 firms are part of a GWAC, that does not mean they are the 300 best in the industry. They tend to be evaluated on a somewhat arbitrary points system, and many firms game the scoring with joint ventures.

- GSA Schedules: The GSA has multi-award schedule (MAS) contracts issued with many vendors. These have the benefit of the administrative ease of a GWAC. Schedules are available to any qualified vendor, so there is not attempt to make a qualitative selection. Much of our work is under the GSA MAS contract.

- Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA): BPAs operate similar to an IDIQ, but are under the GSA MAS contract. They can be multiple award or single award. Single-award BPAs are helpful when the agency wants flexibility to order additional work but isn’t certain of the level of demand when initiating the contract.

Teaming Structures

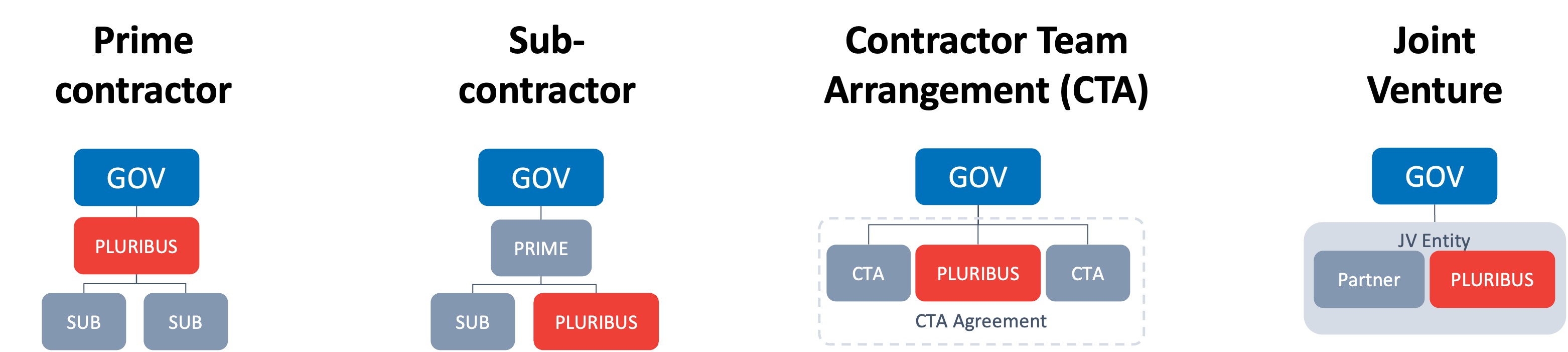

It is common to pursue and deliver work as a team of companies. There are various teaming arrangements, the most typical being a prime/sub arrangement.

- Prime contractor – When Pluribus has a contract directly with the government agency, we are the prime. We may also have subcontractors.

- Subcontractor – Pluribus works under a different company who is the prime. Technically, our customer is the prime.

- Contractor Team Arrangement (CTA) – Multiple companies co-prime under GSA contracts.

- Joint Venture – A special legal entity that lets multiple companies bid as one.

In-team Collaboration: Regardless of the arrangement, we generally follow a “badge-less” delivery model. Day-to-day, it shouldn’t matter much who is from which company.